Last updated January 3, 2025, and based initially on “Making It Work: Setting Up a Regional Anesthesia Program That Provides Value.” The recommendations below represent the author’s opinion only and are not officially endorsed by any medical society or other organization.

Regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine (RAAPM) can add significant non-monetary value to a surgical practice and healthcare system in terms of pain relief, reduced incidence of anesthetic- and opioid-related side effects, and faster recovery (1-4). See “Why We Need Acute Pain Medicine Specialists.” However, gaining this expertise requires an investment of time and money, and the reality at the end of the day is that associating economic value to these procedures may increase their utilization. There are no clear guidelines for developing an efficient RAAPM practice with effective billing strategies in the United States, and the following suggestions are only suggestions based on my experiences setting up programs at two hospitals and are not meant to be prescriptive. Please consult with your practice leadership and billing manager to ensure compliance with billing regulations in your area. Further, actual payment rates will vary between practices due to differences in payor mix.

Communication is key. Before you start implementing changes, meet with your practice leadership and office/department manager to agree on goals, and plan to meet with them on a regular basis. Your practice manager can often provide you with the “big picture” – including the overall direction of your institution. For example, a hospital that performs a high volume of orthopaedic surgery may be genuinely interested in a RAAPM service to reduce recovery room and hospital stays following surgery (5,6). The potential cost savings that result from a reduction in room and board expenditures and downstream utilization may provide value that outweighs minimal revenue generation and may even warrant a stipend from administration to support the practice. If you utilize a billing service, developing a good relationship with the people involved in sending out your charges is essential. Since they are not directly involved in the provision of healthcare, it is vital to a practice to meet them, maintain close communication, supply updated evidence, and clearly explain what you do and why you do it.

Identify your customers. The primary reason for initiating a RAAPM program is to benefit patient care. Hospital administrators are also important customers whose support in the form of personnel, equipment, and training expenses may be necessary for a new RAAPM program to succeed. Your administrators may be very interested in improving patient satisfaction scores related to pain. Our surgical colleagues are customers as well, and surgeons establish contact and begin preparations weeks to months before surgery. Given this long-term doctor-patient relationship, surgeons who support RAAPM can recommend nerve blocks to their patients prior to the day of surgery, leading to reliable patient acceptance. Therefore, surgeons’ concerns regarding regional anesthesia (such as failed blocks, complications, and case delays) must be addressed (7). Finally, your partners in the anesthesiology practice or department must benefit from implementing a RAAPM service. These benefits may be monetary or non-monetary (e.g., securing hospital contracts).

Assess your resources and develop a system. There are many different ways to incorporate RAAPM into an existing anesthesiology practice (8), and it would be impossible to cover each one in detail. The goal should be to develop a practice-specific system that is reliable and consistently available regardless of the anesthesiologist assigned, day of the week, or time of the day. Before you start developing a new RAAPM system, some very important questions should be answered ahead of time.

- Who will perform the procedures and what will be offered? Depending on the goals of the practice, hiring and/or training staff in specific procedural skills and advanced technology (e.g., surface ultrasound, perineural catheter placement) to develop a core group of skilled personnel may be the most important first step. Alternatively, a group may choose a basic set of nerve block procedures that everyone can perform. Residency programs have recently created subspecialty regional anesthesiology rotations, and there are 1-year clinical fellowships which have led to improvements in training (9,10). Fellowship programs may now apply for accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. For anesthesiologists in practice, appropriate training can be obtained by attending conferences and workshops or learning from colleagues who have received specialized training.

- Where will nerve blocks be performed? Commonly, regional anesthesia procedures are performed in the operating room before or after surgery. While this may be the only feasible option for physician-only anesthesiology practices, time in the operating room may be better spent. By performing these procedures in an induction area or preoperative holding room (“block room”) while the preceding case is still in the operating room, operating room efficiency can be improved (11). This parallel-processing model may not work for every group practice or institution as it depends on the availability of resources and personnel (12). For anesthesia groups utilizing a care team (anesthesiologists supervising nurse anesthetists or residents), a block room model is recommended.

- What do you need? Regional anesthesia procedures require specialized equipment (e.g., nerve stimulators, needles, catheter kits, ultrasound machine) and medications, and centralizing supplies will contribute to effective time management. Storing equipment and supplies in one location, either a block room or at least a regional anesthesia block cart, maximizes efficiency.

- How do you “make it work” on the day of surgery? Effective time management in a regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine system is crucial, and advance preparation is essential. Ideally, surgeons begin to discuss postoperative analgesia including regional anesthesia with the patient at the surgical scheduling visit. Alternatively, a preoperative preparation clinic visit or a phone call from the anesthesiologist the day before surgery to discuss specific nerve block techniques can provide patients with early preoperative education to save time and minimize patient anxiety on the day of surgery. You can post educational information for patients online as well – see Regional Anesthesia FAQs. Patients scheduled for surgery amenable to regional anesthesia techniques should be triaged quickly through the admissions process to give the regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine service adequate time to perform procedures.

Design a separate regional anesthesia procedure note. When nerve blocks are performed for postoperative pain, they are considered separate from intraoperative anesthetic care. Therefore, it is worthwhile to design a distinct procedure note or template for an electronic health record (EHR) to document the details of these procedures, physician referral, and indication for the procedure (i.e., pain diagnosis) (13,14). When designing new forms, involve your managers to ensure compliance with current policies and regulations. The American Society of Anesthesiologists has issued a statement on Reporting Postoperative Pain Procedures in Conjunction with Anesthesia.

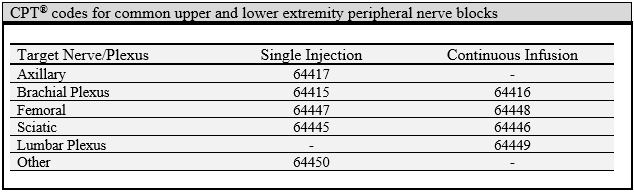

Use appropriate RAAPM Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and modifiers. While anesthesia billing services are very familiar with CPT codes, we cannot expect them to be able to interpret our procedure notes and deduce the appropriate code every time. To prevent confusion, we recommend including current CPT codes on our standardized procedure notes or templates.

When billing for nerve block procedures performed for postoperative pain management, we also include the modifier -59 (distinct procedure) to distinguish the block from the intraoperative anesthetic technique (14). Other pertinent modifiers include -50 (bilateral procedures) and -51 (multiple procedures on the same extremity). Since January 2009, follow-up for continuous nerve block catheters can be claimed for daily evaluation and management (E&M) using 99231-99233 (based on complexity with 99231 being the lowest) for new or established inpatient consults. Daily management of patients with epidural or intrathecal catheters continues to be 01996.

When utilizing real-time ultrasound guidance for nerve block procedures, use CPT code 76942 only if imaging is not already included in the procedural code. Documentation should include an interpretation of findings (limited since this is not a diagnostic code) and reason for using ultrasound (e.g., avoiding vascular puncture). The modifier -26 limits the ultrasound charge to the professional component only. As of January 2023, the following CPT codes now include imaging when used for the procedure: 64415, 64416, 64417, and 64445-8.

Review all updates to CPT coding related to RAAPM every year. Here are additional details on a few select topics.

Paravertebral blocks

- 64461: Paravertebral block (PVB) (paraspinous block), thoracic; single injection site (includes imaging guidance, when performed)

- 64462: Paravertebral block (PVB) (paraspinous block), thoracic; second and any additional injection site(s) (includes imaging guidance, when performed) (This is an add on code and must be billed with 64461)

- 64463: Paravertebral block (PVB) (paraspinous block), thoracic; continuous infusion by catheter (includes imaging guidance, when performed)

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks

- For unilateral TAP blocks (including rectus sheath and variations), use 64486 for single-injection and 64487 for continuous (includes imaging guidance, when performed).

- For bilateral TAP blocks (including rectus sheath and variations), use 64488 for single-injection and 64489 for continuous (includes imaging guidance, when performed).

- For ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks, use 64425; this code does not include imaging.

- In 2025, the “Introduction/Injection of Anesthetic Agent (Nerve Block), Diagnostic or Therapeutic Somatic Nerves” section subheading was revised and now states: “Codes 64486, 64487, 64488, 64489 describe injection of an abdominal fascial plane block.” This indicates that the TAP block codes starting in 2025 may be used for other abdominal fascial plane blocks (e.g., quadratus lumborum block). See the December 2024 ASA Monitor article for more information.

Adductor canal blocks and catheters

- There is no specific “adductor canal block” CPT code. However, this procedure has been described as a “selective femoral” (16) nerve block technique. Anatomically, the common approaches for “adductor canal” blocks describe insertion sites that are located within the femoral triangle and target major branches of the femoral nerve (17). CPT Assistant has advised the use of 64447 for single-injection and 64448 for continuous adductor canal blocks.

- An isolated saphenous nerve block performed distally may be coded using 64450 (other peripheral nerve block).

Genicular nerve blocks of the knee

- For anesthesiologists who have incorporated specific genicular nerve blocks for major knee surgery, there is a code for this: 64454 – Injection(s), anesthetic agent(s) and/or steroid; genicular nerve branches, including imaging guidance, when performed.

- This one code encompasses separate injections of the superolateral, superomedial and inferomedial genicular nerve branches.

Other fascial plane blocks

A joint ASRA-ESRA consensus for nomenclature of fascial plane blocks is available and useful for clarifying block names and definitions (18). In 2025, new CPT codes for fascial plane blocks were published and are structured similar to the TAP block codes.

- For unilateral thoracic fascial plane blocks (e.g., erector spinae plane block), use 64466 for single-injection and 64467 for continuous (includes imaging guidance, when performed).

- For bilateral thoracic fascial plane blocks (e.g., erector spinae plane block), use 64468 for single-injection and 64469 for continuous (includes imaging guidance, when performed).

- For unilateral lower extremity fascial plane blocks (e.g., suprainguinal fascia iliaca block, IPACK), use 64473 for single-injection and 64474 for continuous (includes imaging guidance, when performed).

ICD-10 officially launched in October 2015. Diagnosis codes now include laterality when applicable. For example, pain in right knee is M25.561 while pain in left knee is M25.562. Acute post-thoracotomy pain is G89.12. A possibly useful one to remember is G89.18 (other acute postprocedural pain). Check diagnosis codes carefully, and search when in doubt.

As the management of perioperative pain has evolved, there has been increasing interest in transitional pain services. For complex preoperative preparation of patients in this setting, evaluation and management may qualify as a separate service from the routine preanesthesia workup. The American Society of Anesthesiologists has provided some guidance on distinguishing this type of service.

In summary, setting up a new RAAPM system takes a hands-on approach but greatly improves surgical programs and patient care. Meet with your practice manager and billing service early to open lines of communication. Assess your resources and invest at least as much time in designing your practice model as you will in developing your technical expertise. Although actual payments will vary between institutions and geographic locations, incorporating RAAPM into an anesthesiology practice will add value in addition to controlling costs for the hospital in many ways and providing higher quality recovery for patients. For more information, read my post about value-based purchasing (“pay-for-performance”) and how this influences acute pain management.

Further reading:

- Richman JM, Liu SS, Courpas G, Wong R, Rowlingson AJ, McGready J, Cohen SR, Wu CL. Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 248-57

- Hadzic A, Williams BA, Karaca PE, Hobeika P, Unis G, Dermksian J, Yufa M, Thys DM, Santos AC. For outpatient rotator cuff surgery, nerve block anesthesia provides superior same-day recovery over general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2005; 102: 1001-7

- Hadzic A, Arliss J, Kerimoglu B, Karaca PE, Yufa M, Claudio RE, Vloka JD, Rosenquist R, Santos AC, Thys DM. A comparison of infraclavicular nerve block versus general anesthesia for hand and wrist day-case surgeries. Anesthesiology 2004; 101: 127-32

- Hadzic A, Karaca PE, Hobeika P, Unis G, Dermksian J, Yufa M, Claudio R, Vloka JD, Santos AC, Thys DM. Peripheral nerve blocks result in superior recovery profile compared with general anesthesia in outpatient knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 976-81

- Williams BA, Kentor ML, Vogt MT, Vogt WB, Coley KC, Williams JP, Roberts MS, Chelly JE, Harner CD, Fu FH. Economics of nerve block pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: potential hospital cost savings via associated postanesthesia care unit bypass and same-day discharge. Anesthesiology 2004; 100: 697-706

- Ilfeld BM, Mariano ER, Williams BA, Woodard JN, Macario A. Hospitalization costs of total knee arthroplasty with a continuous femoral nerve block provided only in the hospital versus on an ambulatory basis: a retrospective, case-control, cost-minimization analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007; 32: 46-54

- Oldman M, McCartney CJ, Leung A, Rawson R, Perlas A, Gadsden J, Chan VW. A survey of orthopedic surgeons’ attitudes and knowledge regarding regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2004; 98: 1486-90

- Mariano ER. Making it work: setting up a regional anesthesia program that provides value. Anesthesiol Clin 2008; 26: 681-92, vi

- Richman JM, Stearns JD, Rowlingson AJ, Wu CL, McFarland EG. The introduction of a regional anesthesia rotation: effect on resident education and operating room efficiency. J Clin Anesth 2006; 18: 240-1

- Martin G, Lineberger CK, MacLeod DB, El-Moalem HE, Breslin DS, Hardman D, D’Ercole F. A new teaching model for resident training in regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 1423-7

- Armstrong KP, Cherry RA. Brachial plexus anesthesia compared to general anesthesia when a block room is available. Can J Anaesth 2004; 51: 41-4

- Drolet P, Girard M. Regional anesthesia, block room and efficiency: putting things in perspective. Can J Anaesth 2004; 51: 1-5

- Gerancher JC, Viscusi ER, Liguori GA, McCartney CJ, Williams BA, Ilfeld BM, Grant SA, Hebl JR, Hadzic A. Development of a standardized peripheral nerve block procedure note form. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005; 30: 67-71

- Greger J, Williams BA. Billing for outpatient regional anesthesia services in the United States. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2005; 43: 33-41

- Kim TW, Mariano ER. Updated guide to billing for regional anesthesia (United States). Int Anesthesiol Clin 2011; 49: 84-93

- Ishiguro S, Yokochi A, Yoshioka K, Asano N, Deguchi A, Iwasaki Y, Sudo A, Maruyama K. Technical communication: anatomy and clinical implications of ultrasound-guided selective femoral nerve block. Anesth Analg. 2012 Dec;115(6):1467-70

- Wong WY, Bjørn S, Strid JM, Børglum J, Bendtsen TF. Defining the Location of the Adductor Canal Using Ultrasound. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017 Mar/Apr;42(2):241-245

- El-Boghdadly K, Wolmarans M, Stengel AD, et al. Standardizing nomenclature in regional anesthesia: an ASRA-ESRA Delphi consensus study of abdominal wall, paraspinal, and chest wall blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021 Jul;46(7):571-580