The concept of preoperative preparation for patients scheduled for surgery requiring anesthesia is not a new one. In fact, the idea goes back to Dr. Albert Lee’s description in 1949 (1, 2). Dr. Lee had observed in his day that patients commonly presented for surgery in various states of poor health; it seemed to make more sense to see these patients before surgery to identify areas of concern early and optimize patients’ conditions they went under the knife.

The concept of preoperative preparation for patients scheduled for surgery requiring anesthesia is not a new one. In fact, the idea goes back to Dr. Albert Lee’s description in 1949 (1, 2). Dr. Lee had observed in his day that patients commonly presented for surgery in various states of poor health; it seemed to make more sense to see these patients before surgery to identify areas of concern early and optimize patients’ conditions they went under the knife.

The model of a stand-alone preoperative evaluation clinic, often run by anesthesiology staff, with a “one stop shop” model for patients’ interviews and examinations, testing, education, and referrals really did not take off until the 1990s (3). This patient-centered care model was intended to improve efficiency by decreasing the run-around that many patients encountered, but it also saved money for the institution by reducing the ordering of unnecessary tests (4) and decreasing day-of-surgery cancellations (4, 5).

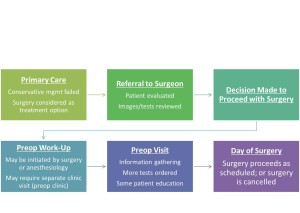

In the present state (assuming an ACO or HMO model), patients are referred to the surgeon by the primary care physician for evaluation of a problem that may be amenable to surgical correction. If the surgeon deems the patient a surgical candidate, the patient may receive a scheduled date for surgery and then may be referred to the anesthesiology preoperative evaluation clinic (“preop clinic”) for further work-up. During this encounter, the provider in the preop clinic may request a variety of tests based on the planned surgery and the patient’s comorbid conditions in order to make appropriate recommendations regarding perioperative management to minimize risks. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published a recent (2012) practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation to guide this process.

Unfortunately, after nearly 2 decades of employing this model, day of surgery cancellations still occur at various rates around the world. Some of the reasons are related to factors that preop clinics were meant to avoid: inadequate preoperative work-up or change in medical condition (6). Other reasons are patient-driven: patients’ not showing up (7) or patients’ changing their minds about having surgery (8). Although not all of these issues are easily solved, it does make me wonder–perhaps it is time for us to rethink the process of preparing patients for surgery.

In our current state, a patient may hypothetically be scheduled for surgery in 8 weeks, a date agreed upon by the patient and surgeon based on available dates. Even if a preop clinic visit takes place the same day as the surgery clinic visit, this only allows 2 months to optimize a patient’s chronic medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease) that took years to develop. Imagine if the timeline was even shorter, like 3 weeks. Add to this time pressure the tremendous physiologic stress that surgery and the subsequent rehabilitation put on the body, and it is not difficult to see why patients can still be cancelled on the day of surgery when they present with abnormal vital signs or test results, making the risks seem too high. We would not expect ourselves to run a marathon without adequate training and preparation on short notice–why would we do this to our patients having elective surgery?

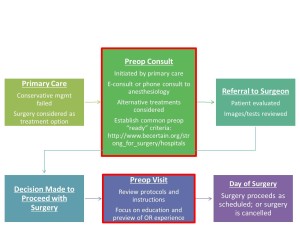

How can we improve preoperative preparation? I think it still starts with the primary care physician. With advances in technology such as telemedicine and e-consults (or low-tech phone calls), we have ways to create a direct interface between primary care physicians and anesthesiologists to discuss advanced preparation of patients who may undergo elective surgical procedures.

This coordinated care model is consistent with ASA’s Perioperative Surgical Home. Early consultation may involve assessment of a patient’s risks and benefits from the procedure, consideration of alternative treatments, and development of a plan to optimize the patient’s comorbid conditions, medication management, and nutrition. Strong for Surgery is a program that provides patients and clinicians useful checklists based on best-available evidence to guide early preoperative preparation related to smoking cessation, nutrition, glycemic control, and medication management. For elective surgery, the decision when to refer the patient to a surgeon can be made jointly by the primary care physician and anesthesiologist. Prior to surgery, the preop clinic visit should still take place, but the focus no longer needs to be on information-gathering and ordering a battery of tests; rather, the goals should be to review pertinent instructions, preview the perioperative experience for patients, and address any logistical or scheduling issues raised by patients to prevent their not showing up or changing their minds at the last minute. Let’s get started.

For more information, check out this brilliant and inspiring video from the Royal College of Anaesthetists “Perioperative Medicine: the Pathway to Better Surgical Care.”

REFERENCES

-

Lee JA. The anaesthetic out-patient clinic. Anaesthesia. 1949 Oct;4(4):169-74.

-

Yen C, Tsai M, Macario A. Preoperative evaluation clinics. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010 Apr;23(2):167-72.

-

Fischer SP. Cost-effective preoperative evaluation and testing. Chest. 1999 May;115(5 Suppl):96S-100S.

-

Fischer SP. Development and effectiveness of an anesthesia preoperative evaluation clinic in a teaching hospital. Anesthesiology. 1996 Jul;85(1):196-206.

-

Ferschl MB, Tung A, Sweitzer B, Huo D, Glick DB. Preoperative clinic visits reduce operating room cancellations and delays. Anesthesiology. 2005 Oct;103(4):855-9.

-

Xue W, Yan Z, Barnett R, Fleisher L, Liu R. Dynamics of Elective Case Cancellation for Inpatient and Outpatient in an Academic Center. J Anesth Clin Res. 2013 May 1;4(5):314.

-

Kumar R, Gandhi R. Reasons for cancellation of operation on the day of intended surgery in a multidisciplinary 500 bedded hospital. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan;28(1):66-9.

-

Caesar U, Karlsson J, Olsson LE, Samuelsson K, Hansson-Olofsson E. Incidence and root causes of cancellations for elective orthopaedic procedures: a single center experience of 17,625 consecutive cases. Patient Saf Surg. 2014 Jun 2;8:24.