It is hard to believe, but this is my last report as CSA President!

We recently held our CSA annual meeting in San Diego which was organized by annual meeting Chair Dr. Christina Menor. This meeting had a theme of “CSA Connect” and was designed to promote more interactive discussion within committees, opportunities to network and catch up with friends and colleagues, meet new people, and enjoy some time to relax. I think this meeting achieved all of these objectives! I have listed a few of my personal highlights and takeaways below.

Annual meeting Vice-Chair Dr. Engy Said put together a fantastic point-of-care ultrasound and regional anesthesia workshop on Thursday. We held very active committee meetings from noon until almost 10 pm (for those on the GASPAC Board), and it was great to see so many members participating in person and virtually thanks to the two new Owl Labs meeting cameras that we recently purchased for CSA. We had a number of special guests in attendance at the annual meeting including past CSA Presidents, one of whom is also our current ASA President Dr. Michael Champeau! We also had the President of the New York State Society of Anesthesiologists, Dr. Jason Lok, and Dr. John Fiadjoe, Executive Vice Chair of Anesthesia at Boston Children’s Hospital and Director of the American Board of Anesthesiology, joining us at the conference.

On Friday, Dr. Cesar Padilla from Stanford gave a compelling presentation on his project to develop and promote Spanish language patient educational video content through a joint venture between Stanford and YouTube. He then introduced our keynote speaker, California Surgeon General Dr. Diana Ramos, who discussed the work being done in California to decrease maternal morbidity and mortality and how we as anesthesiologists can be leaders in this domain. We had so many talented speakers from multiple institutions throughout the state who presented on various topics relevant to anesthesiology, critical care and perioperative medicine, and pain management. After the end of the day’s programming, we had a fantastic networking reception, which Dr. Ron Pearl kicked off as the first of our 75th Anniversary events.

I gave out the first annual CSA President’s Impact Awards to recognize CSA members for the amazing work they are doing. Here are the winners!

- Educator of the Year: Dr. Sophia Poorsattar, UCLA

- Physician Advocate of the Year: Dr. Todd Primack, Vituity

- Clinical Innovator of the Year: Dr. Arash Motamed, USC

- Rising Star: Dr. John Patton, UCLA

- In-Training Physician of the Year: Dr. Abbey Smith, UC Davis

CSA President-Elect Dr. Tony Hernandez Conte led off the Saturday session with an overview of advocacy efforts by CSA and current legislative issues affecting anesthesiology and pain medicine. Then I had the privilege of introducing our honorary CSA Leffingwell Lecturer, Dr. Linda Mason, who has been one of my most influential mentors and sponsors. She is a true icon in our specialty and a role model. Her advice about a career not being a straight line, “There are squiggly lines too,” resonated with so many attendees. She even provided her own assessment of the top 10 challenges facing women in leadership and gave some advice about how to be successful. For anyone interested in hearing more from Dr. Mason as well as some other inspirational anesthesiologists, see these video interviews posted by Dr. Allison Fernandez for the Women of Impact in Anesthesiology project.

Attendees for the annual meeting even stayed until the end on Sunday! We had great talks on patient safety and communications, diversity and inclusion, pain management, and regional anesthesia. Then those of us on the Board of Directors closed out the meeting weekend with a very productive session with a fair amount of debate and discussion that will result in some action items for this June House of Delegates.

What else has CSA been up to in recent months?

The CSA website task force has been working closely with website and brand marketing experts to completely redesign the CSA website to make it faster, reflective of the society, and responsive to member needs. The task force is on track to launch the new website by June.

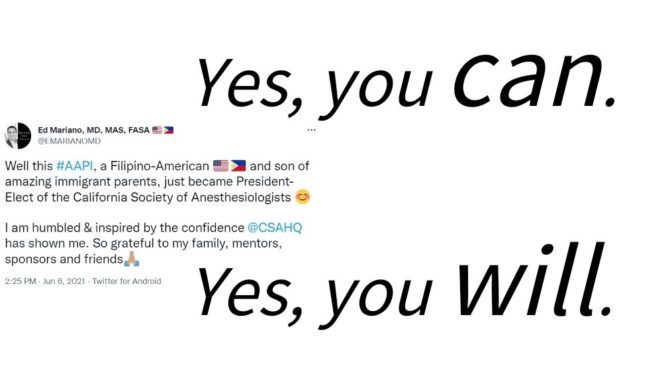

The CSA Communications Committee, chaired by Dr. Emily Methangkool and in partnership with KP Public Affairs, has increased its production of high quality content in a variety of formats, from social media to print media, to promote the value of anesthesiologists’ work and the profession of anesthesiology. Check out recent CSA Vital Times podcast episodes on perioperative work culture and a special interview with Dr. Sharon Ashley in honor of Black History Month in February. The CSA Online First blog posts new content every week! Recent posts have featured CSA members’ activities in research, clinical informatics and global health and member profiles of CSA’s women leaders during the Women’s History Month Spotlight series in March. The CSA Vital Times magazine under the editorship of Dr. Rita Agarwal has produced another fantastic issue that is full of society updates, highlights from each anesthesiology residency program in California, and special articles by CSA members on artificial intelligence, global engagement, Project Lead the Way and other community outreach programs, and the history of anesthesiology in recognition of the contributions of California’s anesthesiologists during this Diamond Jubilee 75th anniversary year.

The week of January 29 through February 4 was designated Physician Anesthesiologists Week in California by an unanimous vote in the Assembly. Assemblymember Matt Haney presented Assembly Concurrent Resolution 3 from the floor, stating that “Anesthesiologists are guardians of patient safety in the operating room, in the delivery room, in the intensive care unit, in pain management clinics, and on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are an essential profession in the healthcare industry. For their dedication to their patients, it is our honor to recognize them for the work they do to care for us.”

So what’s to come between now and the end of my term as President? We continue to work our legislative contacts to advance our advocacy efforts. We are developing more digital image and video content to highlight the importance of anesthesiologists in improving patient experience and outcomes over the course of history and in the present. We are promoting the next CSA annual meeting to be held at the Disneyland Hotel next April 4-7, 2024. We are preparing for the end of the academic year and are promoting the early career membership program for CSA and ASA to keep our soon-to-be graduates engaged in organized medicine.

I cannot be more excited for the upcoming governance year as Dr. Tony Hernandez Conte takes over as President. He has been a fantastic partner this year, and I have learned so much from him. As I wrap up, I will conclude by saying again how proud I am of all the work we have accomplished in advancing the mission of the society this past year. We have stayed true to our identity as an organization representing the great specialty of anesthesiology, anesthesiologists in California, and our patients. I wish to thank to all of our CSA physician volunteers, association management staff members (especially Dave Butler, Megan MacNee, Rachel Hickerson, Dena Silva, Evan Wise, Denise King, Kate Peyser, and Jonathan Flom who got frequent messages from me all year), Alison MacLeod at KP Public Affairs and Bryce Docherty at TDG Strategies on behalf of CSA for the tremendous amount of personal effort and dedication that it takes to keep this organization mission-focused and moving forward.

Facebook

LinkedIn

Pinterest

E-mail

Related Posts: