I had the privilege of co-chairing the 2021 Pain Summit hosted by American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). In the months preceding the summit, ASA physician volunteers and staff as well as representatives from 14 other surgical specialty and healthcare organizations worked towards achieving consensus on a common set of principles to guide physicians and other clinicians who manage acute perioperative pain.

These 7 proposed principles are:

- Conduct a preoperative evaluation including assessment of medical and psychological conditions, concomitant medications, history of chronic pain, substance abuse disorder, and previous postoperative treatment regimens and responses, to guide the perioperative pain management plan.

- Use a validated pain assessment tool to track responses to postoperative pain treatments and adjust treatment plans accordingly.

- Offer multimodal analgesia, or the use of a variety of analgesic medications and techniques combined with nonpharmacological interventions, for the treatment of postoperative pain in adults.

- Provide patient and family-centered, individually tailored education to the patient (and/or responsible caregiver), including information on treatment options for managing postoperative pain, and document the plan and goals for postoperative pain management.

- Provide education to all patients (adult) and primary caregivers on the pain treatment plan, including proper storage and disposal of opioids and tapering of analgesics after hospital discharge.

- Adjust the pain management plan based on adequacy of pain relief and presence of adverse events.

- Have access to consultation with a pain specialist for patients who have inadequately controlled postoperative pain or at high risk of inadequately controlled postoperative pain at their facilities (e.g., long-term opioid therapy, history of substance use disorder).

This is the first project from this new collaborative, which focused on the adult surgical patient, and there are already plans for future projects. The participating organizations are:

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

- American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- American College of Surgeons

- American Hospital Association

- American Medical Association

- American Society of Breast Surgeons

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons

- American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

- American Urological Association

- Society of Thoracic Surgeons

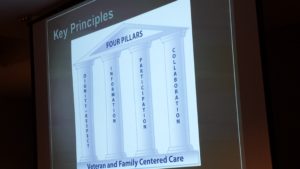

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Changing physician behavior is rarely easy, and studies show that it can take

Changing physician behavior is rarely easy, and studies show that it can take