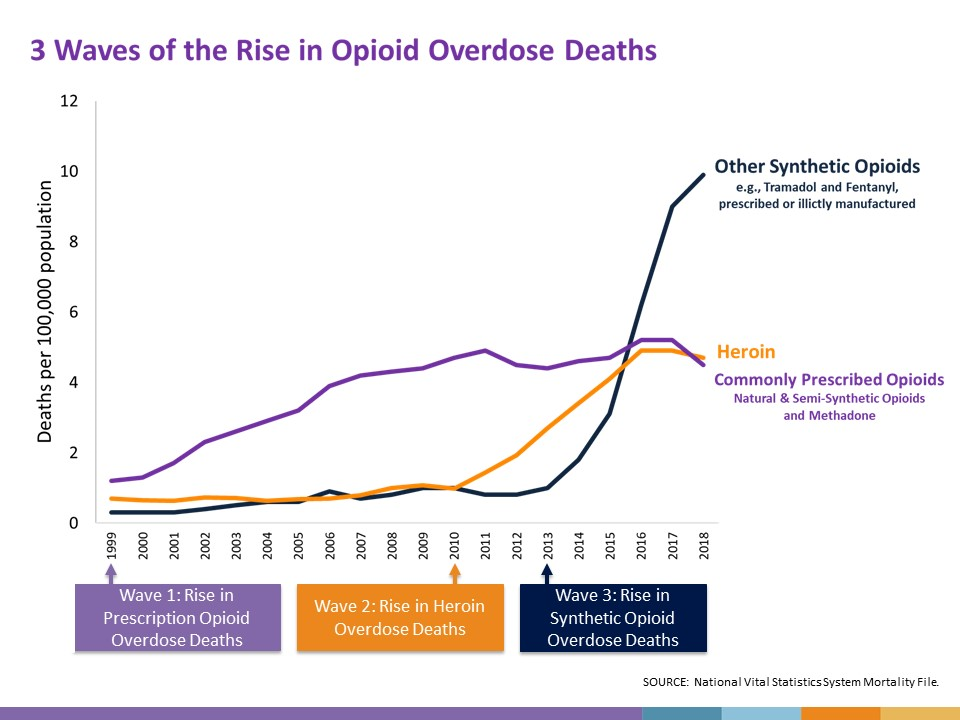

The crisis of prescription opioid overuse and abuse has affected countries around the world, and anesthesiologists are well-positioned to make positive changes (1). Even minor outpatient surgical procedures, and their associated anesthesia and analgesia techniques, can lead to long-term opioid use (2,3). Patients who present for surgery with an active opioid prescription are very likely to still be on opioids after a year (4).

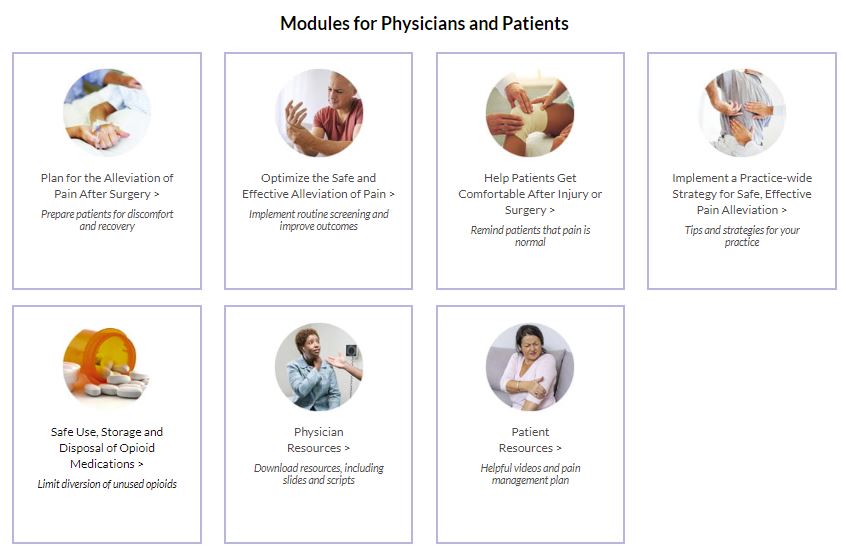

Anesthesiologists have been working to set up regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine programs with careful coordination of inpatient and outpatient pain management to improve patient outcomes. Regional anesthesia, especially with continuous peripheral nerve block (CPNB) techniques, has been shown repeatedly to reduce patients’ need for opioid analgesia (5).

Today, the crisis of drug shortages threatens to reverse the many advances in perioperative pain control that have been achieved. Local anesthetics or “numbing medications” represent a class of drugs that is our strongest weapon against opioids. These drugs (e.g., bupivacaine, lidocaine, ropivacaine) are currently in shortage. Targeted injections of local anesthetic in the form of regional anesthesia eliminate sensation at the site of surgery and can obviate the need for injectable opioids (e.g., fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine) which also happen to be in short supply. Local anesthetics are also the critical ingredient in providing epidural pain relief and spinal anesthesia for childbirth. Without them, new moms will miss the first moments of their babies’ lives.

The following are potential ramifications of the current drug shortages affecting anesthesia and pain management on patient care:

Decreased Quality of Acute Pain Management

Regional anesthesia techniques, which include spinal, epidural, and peripheral nerve blocks, offer patients many potential advantages in the perioperative and peripartum period. Human studies have demonstrated the following benefits: decreased pain, nausea and vomiting, and time spent in the recovery room (6,7). Long-acting local anesthetics (e.g., bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine) generally provide analgesia of similar duration for 24 hours or less (8-11). These clinical effects of nerve blocks typically last long enough for patients to meet discharge eligibility from recovery and avoid unnecessary hospitalization for pain control (12). CPNB techniques (also known as perineural catheters) permit delivery of local anesthetic solutions to the site of a peripheral nerve on an ongoing basis (13). Portable infusion devices can deliver a solution of plain local anesthetic for days after surgery, often with the ability to titrate the dose up and down or even stop the infusion temporarily when patients feel too numb (14,15). In a meta-analysis comparing CPNB to single-injection peripheral nerve blocks in humans, CPNB results in lower patient-reported worst pain scores and pain scores at rest on postoperative day (POD) 0, 1, and 2 (16). Patients who receive CPNB also experience less nausea, consume less opioids, sleep better, and are more satisfied with pain management (16). By using local anesthetic medication to interrupt nerve transmission along peripheral nerves, patients continue to experience decreased sensation as long as the infusion is running. A shortage of local anesthetic medications makes it impossible for anesthesiologists to provide this potent form of opioid-sparing pain control for all surgical patients. This also means that local anesthetics cannot be administered by surgeons as wound infiltration to help patients with incisional pain, and epidural analgesia for laboring women may not be universally available.

Increased Incidence of Postoperative Complications

Based on the study by Memtsoudis and colleagues, overall 30-day mortality for total knee arthroplasty patients is lower for patients who receive regional anesthesia, either neuraxial and combined neuraxial-general anesthesia, compared to general anesthesia alone (17). In most categories, the rates of occurrence of in-hospital complications (e.g. all-cause infections, pulmonary, cardiovascular, acute renal failure) are also lower for the neuraxial and combined neuraxial-general anesthesia groups vs. the general anesthesia only group, and transfusion requirements are lowest for neuraxial anesthesia patients compared to all other groups (17). The inability to offer regional anesthesia (e.g., spinal or epidural) to all patients due to lack of local anesthetics therefore represents a threat to patient safety.

Increased Risk of Persistent Postsurgical Pain

Chronic pain may develop after many common operations including breast surgery, cesarean delivery, hernia repair, thoracic surgery, and amputation and is associated with severe acute pain in the postoperative period (18). A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis reviewed published studies on this subject, and the results favor epidural analgesia for prevention of persistent postsurgical pain (PPSP) after thoracotomy and favor paravertebral block for prevention of PPSP after breast cancer surgery at 6 months (19). Only regional blockade with local anesthetics can block patients’ sensation during and after surgery. Without local anesthetics for nerve blocks, spinals, and epidurals, patients will experience greater than expected acute pain, require additional opioid treatment, and potentially be at higher risk of developing chronic pain.

Increased Health Care Costs

Approximately 31% of costs related to inpatient perioperative care is attributable to the ward admission (20). Anesthesiologists as perioperative physicians have an opportunity to influence the cost of surgical care by decreasing hospital length of stay through effective pain management and by developing coordinated multi-disciplinary clinical pathways (21,22). Regional anesthesia and analgesia can improve outcomes through integration into clinical pathways that involve a multipronged approach to streamlining surgical care (23,24). Inadequate pain control can delay rehabilitation, prolong hospital admissions, increase the rate of readmissions (25), and increase the costs of hospitalization for surgical patients.

In summary, regional anesthesia and analgesia has been shown in multiple studies to improve outcomes for obstetric and surgical patients. The current shortage of local anesthetics and other analgesic medications negatively affects quality of care and pain management and is a threat to patient safety.

References

- Alam A, Juurlink DN. The prescription opioid epidemic: an overview for anesthesiologists. Can J Anaesth 2016;63:61-8.

- Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA internal medicine 2016;176:1286-93.

- Rozet I, Nishio I, Robbertze R, Rotter D, Chansky H, Hernandez AV. Prolonged opioid use after knee arthroscopy in military veterans. Anesth Analg 2014;119:454-9.

- Mudumbai SC, Oliva EM, Lewis ET, Trafton J, Posner D, Mariano ER, Stafford RS, Wagner T, Clark JD. Time-to-Cessation of Postoperative Opioids: A Population-Level Analysis of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Pain Med 2016;17:1732-43.

- Richman JM, Liu SS, Courpas G, Wong R, Rowlingson AJ, McGready J, Cohen SR, Wu CL. Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2006;102:248-57.

- Liu SS, Strodtbeck WM, Richman JM, Wu CL. A comparison of regional versus general anesthesia for ambulatory anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1634-42.

- McCartney CJ, Brull R, Chan VW, Katz J, Abbas S, Graham B, Nova H, Rawson R, Anastakis DJ, von Schroeder H. Early but no long-term benefit of regional compared with general anesthesia for ambulatory hand surgery. Anesthesiology 2004;101:461-7.

- Casati A, Borghi B, Fanelli G, Cerchierini E, Santorsola R, Sassoli V, Grispigni C, Torri G. A double-blinded, randomized comparison of either 0.5% levobupivacaine or 0.5% ropivacaine for sciatic nerve block. Anesth Analg 2002;94:987-90, table of contents.

- Hickey R, Hoffman J, Ramamurthy S. A comparison of ropivacaine 0.5% and bupivacaine 0.5% for brachial plexus block. Anesthesiology 1991;74:639-42.

- Klein SM, Greengrass RA, Steele SM, D’Ercole FJ, Speer KP, Gleason DH, DeLong ER, Warner DS. A comparison of 0.5% bupivacaine, 0.5% ropivacaine, and 0.75% ropivacaine for interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg 1998;87:1316-9.

- Fanelli G, Casati A, Beccaria P, Aldegheri G, Berti M, Tarantino F, Torri G. A double-blind comparison of ropivacaine, bupivacaine, and mepivacaine during sciatic and femoral nerve blockade. Anesth Analg 1998;87:597-600.

- Williams BA, Kentor ML, Vogt MT, Williams JP, Chelly JE, Valalik S, Harner CD, Fu FH. Femoral-sciatic nerve blocks for complex outpatient knee surgery are associated with less postoperative pain before same-day discharge: a review of 1,200 consecutive cases from the period 1996-1999. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1206-13.

- Ilfeld BM. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks: a review of the published evidence. Anesth Analg 2011;113:904-25.

- Ilfeld BM. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in the hospital and at home. Anesthesiol Clin 2011;29:193-211.

- Ilfeld BM, Enneking FK. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks at home: a review. Anesth Analg 2005;100:1822-33.

- Bingham AE, Fu R, Horn JL, Abrahams MS. Continuous peripheral nerve block compared with single-injection peripheral nerve block: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012;37:583-94.

- Memtsoudis SG, Sun X, Chiu YL, Stundner O, Liu SS, Banerjee S, Mazumdar M, Sharrock NE. Perioperative comparative effectiveness of anesthetic technique in orthopedic patients. Anesthesiology 2013;118:1046-58.

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367:1618-25.

- Andreae MH, Andreae DA. Regional anaesthesia to prevent chronic pain after surgery: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:711-20.

- Macario A, Vitez TS, Dunn B, McDonald T. Where are the costs in perioperative care? Analysis of hospital costs and charges for inpatient surgical care. Anesthesiology 1995;83:1138-44.

- Ilfeld BM, Mariano ER, Williams BA, Woodard JN, Macario A. Hospitalization costs of total knee arthroplasty with a continuous femoral nerve block provided only in the hospital versus on an ambulatory basis: a retrospective, case-control, cost-minimization analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007;32:46-54.

- Jakobsen DH, Sonne E, Andreasen J, Kehlet H. Convalescence after colonic surgery with fast-track vs conventional care. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland 2006;8:683-7.

- Macario A, Horne M, Goodman S, Vitez T, Dexter F, Heinen R, Brown B. The effect of a perioperative clinical pathway for knee replacement surgery on hospital costs. Anesth Analg 1998;86:978-84.

- Hebl JR, Kopp SL, Ali MH, Horlocker TT, Dilger JA, Lennon RL, Williams BA, Hanssen AD, Pagnano MW. A comprehensive anesthesia protocol that emphasizes peripheral nerve blockade for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87 Suppl 2:63-70.

- Hernandez-Boussard T, Graham LA, Desai K, Wahl TS, Aucoin E, Richman JS, Morris MS, Itani KM, Telford GL, Hawn MT. The Fifth Vital Sign: Postoperative Pain Predicts 30-day Readmissions and Subsequent Emergency Department Visits. Ann Surg 2017;266:516-24.

Facebook

LinkedIn

Pinterest

E-mail

Related Posts: