Originally included in my editorial for the May 2014 issue of ASRA News.

I make checklists for everything. Whenever I go on a trip, I use the same packing checklist to make sure I don’t forget anything – umbrella, jacket, socks, snacks, passport, and a few other things. Using a checklist not only ensures that I bring everything I’m going to need on the trip; I’m convinced that it makes my packing ritual faster because I don’t have to keep going back and forth to my suitcase whenever I suddenly remember something I left out. Even our dog has her own packing checklist for trips to her sitter’s house. Now that my wife and I have 2 kids, the traveling checklist has gotten more complex and even more essential.

I make checklists for everything. Whenever I go on a trip, I use the same packing checklist to make sure I don’t forget anything – umbrella, jacket, socks, snacks, passport, and a few other things. Using a checklist not only ensures that I bring everything I’m going to need on the trip; I’m convinced that it makes my packing ritual faster because I don’t have to keep going back and forth to my suitcase whenever I suddenly remember something I left out. Even our dog has her own packing checklist for trips to her sitter’s house. Now that my wife and I have 2 kids, the traveling checklist has gotten more complex and even more essential.

As an anesthesiologist, I believe that checklists are part of our culture whether we state them explicitly or not. When I first started my training as a new anesthesiology resident, I learned a mnemonic “MOM SAID” (although there are variations) to check and set up my anesthesia workstation before every case. Each letter stood for an important element of my preparation checklist: Machine Oxygen Monitors Suction Airway IV Drugs. I would then follow this mnemonic with reminders for myself; for example “MOM SAID, ‘don’t forget your stethoscope’” or “MOM SAID, ‘don’t forget to print a baseline EKG strip.’” Over the years, I have found modified forms of this same checklist to be useful just before and after induction, and I continue to use this method today.

Unfortunately, in the complex environment of surgery and perioperative medicine, there aren’t easy mnemonics for everything, and medical errors happen. The use of a formal checklist for surgical and invasive procedures that promotes interactive discussion among all team members and includes important steps related to the entire surgical episode has been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as part of its global Safe Surgery Saves Lives campaign (http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/). In the May 2014 issue of ASRA News, our Resident Section Committee article by Dr. Jennifer Bunch presents her experience implementing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist abroad.

In regional anesthesiology and pain medicine, one of the most dreaded complications besides nerve injury and local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is the wrong-site block. The risk factors related to this medical error have been well-studied and include patient, physician, procedural, environmental, and system factors (1,2). Despite the best intentions, wrong-site blocks have not gone away (3-5). ASRA has been hard at work developing a standardized pre-procedure checklist for regional anesthesiology that has been published in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. ASRA’s recommended checklist includes the following elements: patient identification with assessment of pertinent medical history, separate verifications of the surgical procedure and block plan, confirmation that appropriate equipment and medications for the block procedure and resuscitation are immediately available, and a pre-procedural time-out. Dr. Mulroy was charged with heading this task force and has been kind enough to summarize ASRA’s checklist project in this issue of ASRA News.

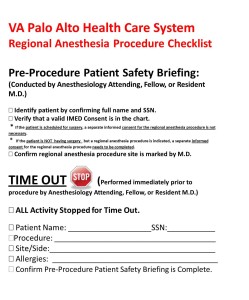

With the publication of this checklist, ASRA is once again taking a stand in support of patient safety. The process of verifying the correct patient, correct site, and correct implants or devices for patients undergoing any invasive procedure, including peripheral nerve blockade, must be consistently and reliably applied for every patient. Since there is no easy mnemonic to help providers remember every step, and the order in which they must occur, I suggest using a standardized cognitive aid for block procedures (Figure 1) that should be posted in a consistent location visible to all providers involved in the procedure and in every location in which these procedures will occur. During the time-out process, it is essential that all team members involved in the patient’s procedure stop what they are doing and actively participate.

When I started my current job in 2010, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) had just issued Directive 2010-023, “Ensuring Correct Surgery and Invasive Procedures,” and this VHA Directive was considered inclusive of regional anesthesia procedures. We have had a process similar to the ASRA checklist in place since then, and I acknowledge that implementing change is hard. Yes, following a checklist requires extra steps. Yes, it may even take more time. The bottom line is – it takes a lot more time, effort, and expense to deal with the complications that may result if you don’t do this. The ASRA checklist is not prescriptive and allows for local institutional interpretation and application. If I routinely use a checklist when I pack my suitcase, I can’t think of any good reason not to use one for the safety of my patients.

References

- O’Neill T, Cherreau P, Bouaziz H. Patient safety in regional anesthesia: preventing wrong-site peripheral nerve block. J Clin Anesth. 2010 Feb;22(1):74-7.

- Cohen SP, Hayek SM, Datta S, Bajwa ZH, Larkin TM, Griffith S, Hobelmann G, Christo PJ, White R. Incidence and root cause analysis of wrong-site pain management procedures: a multicenter study. Anesthesiology. 2010 Mar;112(3):711-8.

- Edmonds CR, Liguori GA, Stanton MA. Two cases of a wrong-site peripheral nerve block and a process to prevent this complication. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005 Jan-Feb;30(1):99-103.

- Stanton MA, Tong-Ngork S, Liguori GA, Edmonds CR. A new approach to preanesthetic site verification after 2 cases of wrong site peripheral nerve blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008 Mar-Apr;33(2):174-7.

- Al-Nasser B. Unintentional side error for continuous sciatic nerve block at the popliteal fossa. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2011;62(4):213-5.