Inscribed on a plaque just below a statue of an eagle in front of my hospital is a famous quote from President Abraham Lincoln that begins, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle….”

Inscribed on a plaque just below a statue of an eagle in front of my hospital is a famous quote from President Abraham Lincoln that begins, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle….”

It is the reason why the Veterans Affairs (VA) system exists. It is the reason why we VA physicians come to work each day.

I am honored to care for our special patient population, and I admit to getting defensive when I hear negative, sensationalistic news about the VA. In truth, VA physicians have good reasons to take pride in their health care system and should be inspired to take on leadership roles.

In 1994, the VA was by far the largest networked health care system in the US. It consisted of 172 acute care hospitals, 350 hospital-based outpatient clinics, 206 counseling facilities, and 39 residential care facilities, with a budget of over $16 billion annually, and was “highly dysfunctional” according to an article co-authored by Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former Under Secretary of Health under President Clinton who headed the VA health care system from 1995-1999.

A decade later, the VA had turned around dramatically. When Philip Longman, a writer with a long interest in health policy, looked for potential solutions to the healthcare crisis in the United States, he found his “muse” within the VA—not in the private sector. He titled his 2007 book about the VA health care system: Best Care Anywhere: Why VA Health Care is Better Than Yours. What happened to make the VA go from worst to first?

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Kizer guided the VA to reset its focus on three core missions:

- Providing medical care to eligible veterans to improve their health and functionality

- Educating healthcare professionals

- Conducting research to improve veteran care.

His strategies led to a dramatic transformation that took less than five years. VA health care showed a statistically-significant improvement in all quality of care indicators after the reengineering when compared to the same indicators before, and these improvements were evident within the first two years. By 2000, the VA outperformed Medicare hospitals on 12 of 13 quality of care indicators. A comprehensive study using RAND Quality Assessment Tools showed that VA adherence to recommended processes of care exceeded a comparable national sample. In terms of surgical care, the VA matched or outperformed non-VA programs in rates of morbidity and mortality.

Integral to this transformation was a remarkable nationwide rollout of an electronic health record in less than three years, with the last facility going live in 1999, long before most health care systems in the United States had even started. Other notable achievements during this period of reengineering included:

- 350,000 fewer inpatient admissions (FY 1999 vs. FY 1995) despite a 24% increase in patients treated overall;

- A decrease in per-patient expenditures by 25%;

- An increase in proportion of surgeries performed on an ambulatory basis (80% in FY 1999 vs. 35% in FY 1995);

- A 10% increase in total number of surgeries performed with a decrease in 30-day morbidity and mortality;

- VA health user satisfaction scores that exceeded the private sector; and

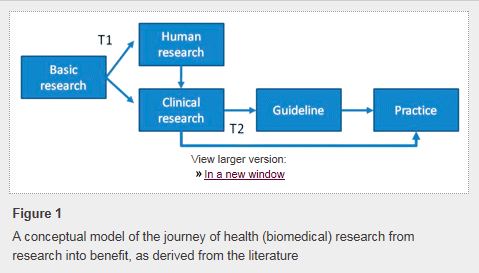

- Realignment of the VA medical research program with establishment of a new translational research program, the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

These achievements were not the result of one person’s efforts. Change implementation required engagement of front line staff, especially the physicians and other health care providers. Unfortunately last year’s VA waitlist scandal raised serious concerns related to veterans’ access to care, scheduling practices, and the reporting of performance metrics. In an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Kizer expressed his concerns regarding variability in the quality of care provided within VA in 2014 when compared to other top-tier integrated healthcare systems. Some VA hospitals performed remarkably well while others did not, and some facilities severely lacked personnel and resources.

Today, there are approximately 9 million veterans enrolled in VA health care, and the VA needs physicians to step up and be leaders. Advanced technology (e.g., secure messaging, e-consultation, and clinical video telehealth) already exists within the VA to streamline communication between patients and physicians and can be used to promote patient-centered, personalized health care and improve access. Some of the highest impact medical research in the world takes place within VA, performed by VA physician scientists, and requires leaders to advocate for continued funding. The results of these studies and others should form the basis of best clinical practices that VA physician leaders need to disseminate and implement at their respective facilities. VA physicians have pioneered the field of simulation education, and this represents one tool that may be used to facilitate dissemination. The VA has arguably the richest and most mature electronic health record in the country, if not the world; yet these data are not easily accessible. Physicians on the front lines of patient care, those engaged in research, and those in leadership positions need to advocate for resources to develop real-time analytics and harness the power of our patients’ data to guide clinical care decisions and make the health care system adaptable to the changing needs of patients.

Today, there are approximately 9 million veterans enrolled in VA health care, and the VA needs physicians to step up and be leaders. Advanced technology (e.g., secure messaging, e-consultation, and clinical video telehealth) already exists within the VA to streamline communication between patients and physicians and can be used to promote patient-centered, personalized health care and improve access. Some of the highest impact medical research in the world takes place within VA, performed by VA physician scientists, and requires leaders to advocate for continued funding. The results of these studies and others should form the basis of best clinical practices that VA physician leaders need to disseminate and implement at their respective facilities. VA physicians have pioneered the field of simulation education, and this represents one tool that may be used to facilitate dissemination. The VA has arguably the richest and most mature electronic health record in the country, if not the world; yet these data are not easily accessible. Physicians on the front lines of patient care, those engaged in research, and those in leadership positions need to advocate for resources to develop real-time analytics and harness the power of our patients’ data to guide clinical care decisions and make the health care system adaptable to the changing needs of patients.

Finally, I call on VA physician leaders to be innovators, designing and studying new interdisciplinary coordinated models of care, to improve outcomes and then share these models with each other. We physicians need to work together as “One VA” to decrease variability within the system and improve quality and value throughout.

This post has also been featured on KevinMD.com.

REFERENCES

- Kizer KW, Dudley RA: Extreme makeover: Transformation of the veterans health care system. Annu Rev Public Health 2009; 30: 313-39

- Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA: Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2218-27

- Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, Hayward RA, Shekelle P, Rubenstein L, Keesey J, Adams J, Kerr EA: Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141: 938-45

- Choi JC, Bakaeen FG, Huh J, Dao TK, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS, Chu D: Outcomes of coronary surgery at a Veterans Affairs hospital versus other hospitals. J Surg Res 2009; 156: 150-4

- Grover FL, Shroyer AL, Hammermeister K, Edwards FH, Ferguson TB, Jr., Dziuban SW, Jr., Cleveland JC, Jr., Clark RE, McDonald G: A decade’s experience with quality improvement in cardiac surgery using the Veterans Affairs and Society of Thoracic Surgeons national databases. Ann Surg 2001; 234: 464-72

- Matula SR, Trivedi AN, Miake-Lye I, Glassman PA, Shekelle P, Asch S: Comparisons of quality of surgical care between the US Department of Veterans Affairs and the private sector. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 211: 823-32

- Bakaeen FG, Blaustein A, Kibbe MR: Health care at the VA: recommendations for change. JAMA 2014; 312: 481-2

- Kizer KW, Jha AK: Restoring trust in VA health care. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 295-7

Facebook

LinkedIn

Pinterest

E-mail

Related Posts:

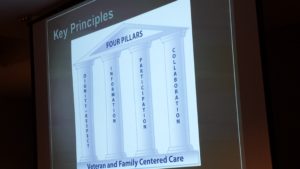

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at

Once a year, our Service organizes a faculty development retreat during which we reassess our mission, vision, strategic priorities, and tactics and work on one or two big ideas. Two years ago in 2015, we invited our VFAC partners to join us at