At our conferences and workshops focused on regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine, we present and discuss the latest and greatest advances in nerve block techniques for patients having surgery. As physicians and scientists, we are very familiar with the evidence supporting the use of nerve blocks for postoperative pain management. We know they are extremely effective in preventing and treating pain, decreasing the need for opioid medications, and even avoiding the common side effects of general anesthesia such as nausea and vomiting and confusion.

We believe in them.

We are passionate about them.

We want all patients to have access to them.

Within the meeting sessions and sometimes in the common spaces outside the lecture halls, regional anesthesiologists often vigorously debate various things like: the best sites and techniques for nerve block injections, needle and catheter equipment, ultrasound transducers and machines, and local anesthetic selection and use of adjuvants among other things.

For knee replacement patients in particular, we want to provide the best form of pain management while maximizing their postoperative function. Since 2011, dozens of research articles have studied the more distal adductor canal block for pain management in patients who undergo knee replacement as a replacement for the long-standing incumbent, the femoral nerve block. In reality, these sites of nerve block placement are mere centimeters apart and represent different sites of injection along the same set of nerves. Anesthesiologists and surgeons continue to debate this issue in person, in social media, and in publications.

It’s time for a reality check.

I had the opportunity to do a big data study with my friend and colleague, Dr. Stavros Memtsoudis. In this study of over 191,000 knee replacement patients who had surgery across over 400 hospitals in the United States, only 12.1% of all patients had a peripheral nerve block of any kind! Over 76% of patients had general anesthesia alone with no other regional analgesic technique.

A more recent study published this month in the Journal of Arthroplasty evaluated over 219,000 patients who underwent knee replacement, and only 27.3% of patients received a peripheral nerve block. The database used for this study was NACOR, operated by the Anesthesia Quality Institute and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. This was brought to my attention through a Tweet sent by My Knee Guide (@mykneeguide).

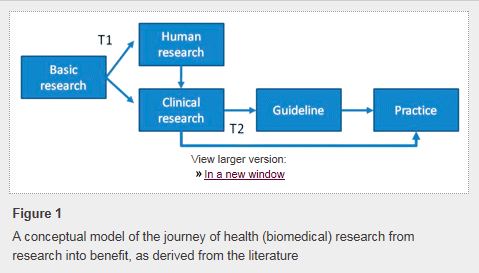

Where is the disconnect? The efficacy of peripheral nerve blocks for pain control in patients having knee arthroplasty was first published more than 25 years ago. It is easy to assume that such well-established evidence is being applied daily in clinical practice for the hundreds of thousands of patients who receive this surgery every year, but it’s not. Today, there is more awareness than ever about the risks of opioids, and nerve blocks offer proven opioid-sparing pain relief. Perhaps this is just another example of the gap separating the “ivory tower” of academics and real life.

In a previous post, I wrote about the obstacles to changing clinical practice, and there are many:

- Lack of awareness (don’t know guidelines exist)

- Lack of familiarity (know guidelines exist but don’t know the details)

- Lack of agreement (don’t agree with recommendations)

- Lack of self-efficacy (don’t think they can do it)

- Lack of outcome expectancy (don’t think it will work)

- Inertia (don’t want to change)

- External barriers (want to change but blocked by system factors)

Maybe it’s time to focus less on debating minor differences in the ways we do blocks and focus more on figuring out how to make sure more patients actually get them.

Many people, even those who work in the operating room every day, take safe anesthesia care for granted. There has been growing pressure recently to abandon the team model and remove physician anesthesiologists’ supervision of nurse anesthetists with the latest threat coming from within

Many people, even those who work in the operating room every day, take safe anesthesia care for granted. There has been growing pressure recently to abandon the team model and remove physician anesthesiologists’ supervision of nurse anesthetists with the latest threat coming from within  We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated,

We all know that not all pain is the same. While chronic pain can sometimes be palliated,  Healthcare around the world is changing. In the United States, healthcare reform has been focused on achieving the “triple aim” as described by Berwick (1). This

Healthcare around the world is changing. In the United States, healthcare reform has been focused on achieving the “triple aim” as described by Berwick (1). This  To date, anesthetic interventions focused on targeting acute pain have not demonstrated long-term functional benefits (12,13). Perhaps implementation of a PSH with better care coordination that includes individualized

To date, anesthetic interventions focused on targeting acute pain have not demonstrated long-term functional benefits (12,13). Perhaps implementation of a PSH with better care coordination that includes individualized